As salmon farming expands, IMAS is frequently asked about the potential for interactions between the salmon industry and Tasmania’s iconic rocky reef ecosystems. Along with having high intrinsic conservational value, temperate reef ecosystems in Tasmania support high value commercial fisheries such as rock lobster and abalone and important recreational fisheries. Through a Fisheries Research and Development Corporation (FRDC) project, we developed techniques to identify if rocky reef ecosystems in Tasmania are becoming stressed from an increase in nutrients (organic enrichment), such as occurs from salmon farming and other human activities.

Methods were tested in two areas where there has been recent expansion of salmon farming: northern Bruny Island and the lower D’Entrecasteaux Channel. Biodiversity was surveyed using techniques established by IMAS scientists Prof Graham Edgar and Dr Neville Barrett. These diver-based surveys provide detailed information on the fish, invertebrate and algal species and abundance on reefs. Data from these biodiversity surveys was used to develop a rapid visual assessment (RVA) technique specifically designed to detect the effects of nutrient enrichment. The challenge with this technique was that it needed to be rapid enough to be undertaken on a regular basis, whilst at the same time being powerful enough to detect changes in the reefs that could be specifically attributable to nutrient enrichment.

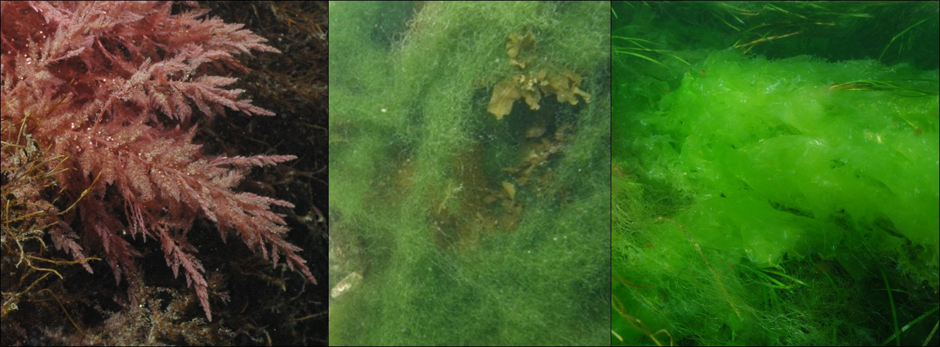

Fourteen key responses were quantified as part of the RVA technique development. Many of these variables focused on algae (seaweed) response, including changes to canopy cover, turfing algae cover and levels of ephemeral and epiphytic algae. Large kelp species such as Phyllospora comosa (cray weed)and Ecklonia radiata (common kelp)are critical in rocky reef ecosystems, forming canopies that influence all other reef fauna and flora in some capacity. As changes in this canopy cover will affect all aspects of the reef community, it is vital to monitor. Also important are turfing algal species, as they are known to flourish when nutrient levels increase, and if present in excess they can change the nature of the reef by trapping sediment and prohibiting the recruitment of canopy-forming kelp species.

Ephemeral and epiphytic algae, such as Ulva (sea lettuce), Chaetomorpha and Asparagopsis take up nutrients far more rapidly than many other algal species and are also indicators of nutrient enrichment. They can respond rapidly to pulses of nutrients, growing very quickly and potentially smothering kelp and other algal species. In spring and late summer, these species are often naturally present in quite large quantities, as they are nature’s own way of dealing with excess nutrients in the system. However, problems can arise when additional nutrients from activities such as salmon aquaculture lead to sustained growth throughout the year. Hence, it is important to monitor more than once a year and outside the normal growing time for these species. The RVA method also incorporates data on sponge cover, coralline algae cover and type, along with a selection of major invertebrate species. We have deliberately targeted variables to monitor which are important to the reef function and can be easily assessed. Changes in all of these response variables can be used to indicate the degree to which rocky reefs are subject to stress from nutrient enrichment.

The initial project is almost at an end and the final report will be available late 2021. Additional projects are now underway, with a student undertaking an Honours project to determine if we can use video sampling instead of divers. Towed video provides less detail and accuracy than diving but is cheaper and a much greater area can be surveyed. This project is looking to validate RVA techniques for undertaking reef surveys using towed cameras and photo-quadrat assessment, examining both advantages and disadvantages of this method.

Through the RVA approach we have developed what could be an important tool to assist with the monitoring and management of the impacts of salmon farming on temperate rocky reefs. To ensure that all sources of change are captured, and to fully assess the effect nutrient enrichment may have on an ecosystem, we would advocate that this approach is best employed in combination with longer-term biodiversity assessments (i.e. “Edgar-Barrett” surveys), and establishment of reliable baselines. Inclusion of a structured reef monitoring program that collects consistent time-series data in both farming/multi-use areas and control locations will provide the opportunity to further validate and refine the RVA tools. It is only with data collected over longer time-frames that we can look to develop subtler threshold levels and tipping points, along with more sensitive impact indicators in these complex and ever-changing systems.